Dude, This is Why the “Big Lebowski: The Musical” Remains but a Dream

One of the great disappointments of the 21st Century surely has to be that the seemingly inevitable Big Lebowski: The Musical has somehow not yet materialized. It is quite obviously a slam dunk idea, and if we are to believe string theory, we are stranded in the one dimension out of thirteen where this glorious reality does not exist. Instead, the little indie film Waitress was improbably turned into a smash hit, while Big Lebowski: The Musical remains but a dream.

Why have we been so forsaken? The only reasonable conclusion is that the formidable ghost of Dude has been standing in the way of Big Lebowski: The Musical taking its rightful place alongside Hamilton and The Book of Mormon as Broadway’s gifts to this, still young (yet, seemingly long-in-the-tooth) century. Dude was the lyricist Gerome Ragni’s follow-up to Hair and has gone down as one of Broadway’s biggest fiascos. The show’s producer Adela Holzer, recently died, once again shaking the grave of Dude. In the early 1970s, the press praised Holzer as a bright, young producer willing to take risks on groundbreaking material. With All Around Town, a farce directed by Dustin Hoffman and Terrence McNally’s The Ritz, she had two hits under her name and was brimming with confidence. “I have three college degrees, and I know if something is good,” she told The New York Times. Talk like that would make even Icarus blush. It was only a matter of time before the world would see her wings burn.

The demise of Dude is not just the tale of a Broadway flop; it may very well be the defining story of the entire genre. It has it all: excess, insane prima donna behavior, outlandish demands, an unscrupulous producer, nudity, revolt, and a quick fall off the cliff.

Adela Holzer had invested in Hair, claiming to have turned a $57,000 investment into a $2,000,000 profit (in actuality, New York magazine reported that she probably turned $7500 into $115,000). A little puffery in the producing class is no big thing, if not a requirement. She and her third husband, a shipping magnate, decided to go all-in with Gerome Ragni, who is the brain behind Dude and was a lyricist of Hair. Hair’s phenomenal success had turned Ragni into a millionaire, and he had scribbled his epic vision of “Dude” across 2000 pages. Had he not just co-written Hair, a 2000 page manuscript for a Broadway musical would have perhaps been a sure sign of an addled, schizophrenic mind, but in this case, it was merely a testament to his overflowing genius.

Adler, in all her producer’s glory, insisted that Ragni cut it down to 200 pages, but by all accounts, there was still no story to be found. Considering how thin the narrative runs through most Broadways, it is surprising that one could not be concocted. But at the time, Gerome Ragni was considered an eccentric genius going deep down the rabbit hole to inevitable glory, and the novice producer indulged most of his outlandish inclinations. In a 1972 Times post-mortem (“Dude … an $800,000 Disaster”), Adler says, “It had no plotline. That worried me a little. I see now it should have worried me more. Basically, Dude was everyman. Everyman who loses his innocence and fights to regain it. But Dude was also Gerry Ragni’s own life. His memories. Temptations. His fears. His struggle to create … when he was five years old he began painting crazy beautiful paintings all over his family’s house and his parents couldn’t stop him. Even then he believed he was a genius. That belief made him tireless … I knew Hair was a traumatic experience for him. He became famous – a rich man. But his marriage broke up and fell in with a strange crowd.”

In Ragni’s original fever dream, he envisioned that Dude would be performed at the Schubert, where the stage and seats would be “scooped out,” and the theater would be reconfigured in the round. But when the producer’s procured his dream venue, he demanded the Imperial Theater instead. Pippin, though was playing there. So, the production had to make do with the Broadway Theater, which was considered cursed, a flop house. Dude was here to break the mold, and the production would be unimpressed by such petty superstitions. The theater was booked; its interior was dismantled and transformed to contain the circus-like, ever-changing spectacle that was rattling about in Ragni’s restless mind.

Holzer initially went along with Ragni and cast one of his friends to portray “Dude”. Not exactly a sign of producorial strength, especially after it was revealed that the actor could not, in fact, sing. This liability would prove to be an issue, and the production had no choice but to fire Ragni’s pal. The logical replacement for the 23-year-old white actor was, amazingly, Ralph Carter, an 11-year-old African American boy. It was a bold decision that must have seemed groundbreaking at the time. Ralph, though, was unable to pull off several of the numbers, so they hired twenty-something white male Nat Morris to play the older dude, aka “Big Dude.” Surely, they had convinced themselves that having a black child and a white adult portray Dude was a brilliant commentary on the duality of man and would reflect that deep down we are all brothers … or something. Although, that may be a bit harsh. After all, Todd Haynes brilliantly used six actors to play Bob Dylan in his 2007 masterpiece I’m Not There.

The lack of a script proved to be a problem during rehearsals. Allan Nichols, who played the God-like character “33” (originally Ragni intended to play this part himself, as he had played Berger, the lead, in the original cast of Hair) was quoted, “By the fourth week of rehearsals, the producers, director, and choreographer had stopped communicating … We didn’t dare discuss the script. There was none!”

Instead, Ragni was preoccupied with badgering his producer with 2 a.m. phone calls, requesting the release of a hundred butterflies at the beginning of his performance. (It should be noted that this is a man who allegedly did not do drugs). Rebuffed by Adler, Ragni pivoted to envisioning the release of live pigs and chickens down the aisles during intermission. That genius notion, too, was a no-go, but Adler did acquiesce to unloading two tons of dirt on the theater floor. It was a decision that left the sometimes naked actors coughing and gasping for air from the plumes of dust and debris. Instead of removing the dirt, they watered it down. Now, covered in mud, the actors’ complaints turned into a cacophony, bordering on out-right revolt. In order to appease the resurrecting players, they replaced the dirt with brown pieces of felt, which soon gave way to brown fragments of plastic.

not impressed

The actors, though, were not satisfied (are they ever?), and lengthy “therapy” sessions were held to air their grievances. Many thought their careers would be over once the world bore witness to the inevitable fiasco. Many thought they might just lose their minds from the never-ending chaos and uncertainty. Ragni’s sister taped the sessions, and presumably, in a counter-culture meta-utopian attempt at understanding, Ragni inserted some of the best complaints into the show … but, sadly, he would later remove them. Similarly, in this autobiographical opus Ragni would also delete all references to his many grievances surrounding Hair, the source of so much money, fame, and, apparently, angst.

There would be previews where the audience couldn’t decipher the lyrics or the dialogue as the theater’s acoustics were not designed for theater in the round … or for dueling bands playing in the balconies. On the first night of previews, it seem the audience was unaccustomed to the charms of an unintelligible musical and begin crying “Rip-Off!” Naturally, the production hired sound engineers from MIT to fix the issue, but alas, their efforts fell short.

As the ship sank, Holzer made one last-ditch effort: hiring a new director, Tom O’Horgan. He had directed Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar, a bone-fide star in his own right. It was a Hail Mary pass that just might connect. The rub was that the hot-shot director only had three weeks to whip Dude into shape before he had to move on to another project. His arrival, though, buoyed the actors, who believed they had found their savior.

While it looked like the production had let the sun shine in with O’Horgan’s star power, the production could not be salvaged. Ragni still had not finished the script, and actors were often left to improvise their own dialogue. Then, oddly, Ragni’s brother – a priest in full regalia – started showing up to rehearsals, vigorously pushing to insert more overt religious imagery and overtones into Dude. O’Horgan resisted the priest’s input, but the holy man persisted … until the producers had no choice but to exorcise him from the theater.

The ever-changing “script” was not frozen until two nights before the official open. Yet, still, there was a feeling that all of the craziness might just pay off. “Audiences love it,” Adler insisted. Summoning the audience’s collective response, the Times mused in its post-mortem: “It was entertaining, sometimes, yes. The songs were great. Yes. But what’s Dude all about?”

The critics would be more brutal: “Boring.” “Infantile.” “Shapeless.” “Much ado about nothing.” The New York Daily News called it “an extremely pretentious and juvenile affair and certainly not worth all the fuss.” Richard Watts of the New York Post really wanted to like it, “But after the first half hour,” he generously surmised, “it made me unhappy.”

The legendary Clive James at The Times praised O’Horgan’s direction: “There is also an almost gothic sense of fantasy to his work; he has the manic imagination and innocence of a child indulging his nightmares in daylight. Mr. Ragni is an artist of the same jib. But here the lack of discipline to that imagination, a freedom that proved so charming in Hair, chains the musical down instead of liberating it. In Hair the very aimlessness of the piece, its random poetry and shafts of insight could afford the luxury of a nonstructure because it was describing a life style that deliberately embraced nonstructured patterns as its aim. Dude, on the other hand, seems to be an allegory about ‘that great theater in the sky’, and an allegory that is not clear, even on its primary level, is in no end of trouble.”

The show would take in only $500 at the box office the next day. Adler insisted that word of mouth was terrific and took out an ad proclaiming that tickets through January 3, 1973, were on sale … But alas, such wishful thinking would not be infectious, and Dude would close after only 16 performances. A glorious disaster.

As the show limped to the end of its run, it is reported that some exasperated audience members fled the theater at intermission only to find themselves confronted by none other than Gerome Ragni. “Get back to your seats!” he yelled. “Go sit down and suffer with everybody else! Suffer!”

For a show that closed so quickly, we can be grateful that the cast album survives. The was recorded in March of 1972, and the show premiered in October of that year. Considering how much Ragni tinkered with the book and the tunes, it is quite possible that the cast album bore little resemblance to the musical that died on Broadway.

After Dude lost $800,000 in 1972 (4.8 million in 2020), about half of which was her and her husband’s investment, Adler declared that her days as a theater producer were over. Her bank-rolling husband complained, “The Broadway system is a lousy system. A bunch of stone-faced old men should not have the right to make up the public’s mind.” But it would turn out that Adela could not kick the Broadway habit so easily. She would go on to produce several more flops, a losing streak that left her paying off investors with money from new investors. On Broadway, such accounting is sometimes just called “producing,” but in real life, it’s called a “Ponzi Scheme.”

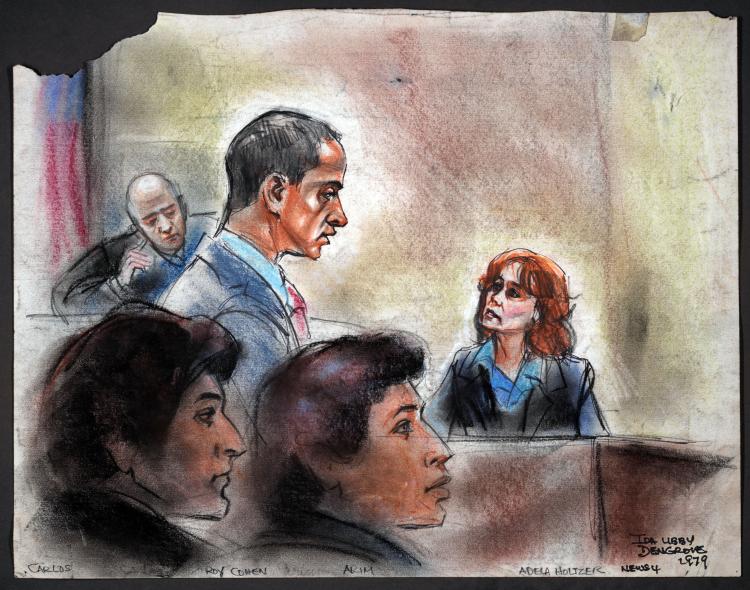

In her first trial in 1977, naturally, her lawyer was Roy Cohn, notorious as Joe McCarthy’s counsel, as well as Donald Trump’s mentor in mendacity. Cohn is truly one of the great scumbags of the 20th Century. In addition to their ginned up crusade against alleged communists, he and McCarthy would purge hundreds of gay men from the U.S. government. While McCarthy was just a drunken asshole full of hate and lies, Cohn – of course – was a closeted gay man. So, if anyone ever deserved to die of AIDS, it was Roy Cohn. And that is exactly what happened. Cohn would later be depicted on his death bed in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, haunted by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg, who was executed in the electric chair after being prosecuted (and/or persecuted) by Cohn.

Adela’s crimes went well beyond bilking Broadway investors, as her scams included fake investments in Indonesian Toyota dealerships and Spanish real estate. Cohn was as worthless to Adela as he was to life itself. She was convicted for fraud and the judge sentenced her to two-six years in the clink. The Ponzi scheme is a time honored scam and she would go to that well again and again. All in all, Adler would end up spending 14 years in prison for fraud and various cons. Most despicably, she would sink to ripping off immigrants from her native Spain. According to The New York Times she “convinced Spanish-speaking immigrants that if they paid her $2,000 to $2,700, she could get prominent political friends in Washington to pass private immigration-relief bills that would give immigrants permanent resident status, the authorities said.”

Sure, any Broadway producer probably has a bit of grifter in their bones, but Adela was in a league of her own. Show business loves larceny, making it virtually inevitable that Terrence McNally – she had produced his work twice – would write a comedy featuring a character based on her larger-than-life persona: It’s Only a Play. The action takes place in a producer’s Upper East Side townhouse as the writer, director, and various actors wait for their play to be reviewed. The play’s most recent incarnation in 2014 starred Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick, featuring Meghan Mullally as Julia Rudder, the hostess and producer inspired by Ms. Holzer.

Is Adela Holzer why we can’t have nice things like Big Lebowski: The Musical ? Yes, I am afraid there really is no other explanation. In essence, she peed on the rug, leaving a long trail of broken dreams in her wake, tragically sullying the idea that the Dude could succeed on Broadway. But now that the witch is dead, perhaps the Dude can rise again? One can only hope that this small blog post will be the proverbial pebble tossed in the ocean, whose ripple will somehow become a tsunami and, only then, will the grandeur and glory of Big Lebowski: The Musical wash over us all.